A new power is loose in the world. It is nowhere and yet it’s everywhere. It knows everything about us – our movements, our thoughts, our desires, our fears, our secrets, who our friends are, our financial status, even how well we sleep at night. We tell it things that we would not whisper to another human being. It shapes our politics, stokes our appetites, loosens our tongues, heightens our moral panics, keeps us entertained (and therefore passive). We engage with it 150 times or more every day, and with every moment of contact we add to the unfathomable wealth of its priesthood. And we worship it because we are, somehow, mesmerised by it.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

In other words, we are all members of the Church of Technopoly, and what we worship is digital technology. Most of us are so happy in our obeisance to this new power that we spend an average of 50 minutes on our daily devotion to Facebook alone without a flicker of concern. It makes us feel modern, connected, empowered, sophisticated and informed.

Suppose, though, you were one of a minority who was becoming assailed by doubt – stumbling towards the conclusion that what you once thought of as liberating might actually be malign and dangerous. But yet everywhere you look you see only happy-clappy believers. How would you go about convincing the world that it was in the grip of a power that was deeply hypocritical and corrupt? Especially when that power apparently offers salvation and self-realisation for those who worship at its sites?

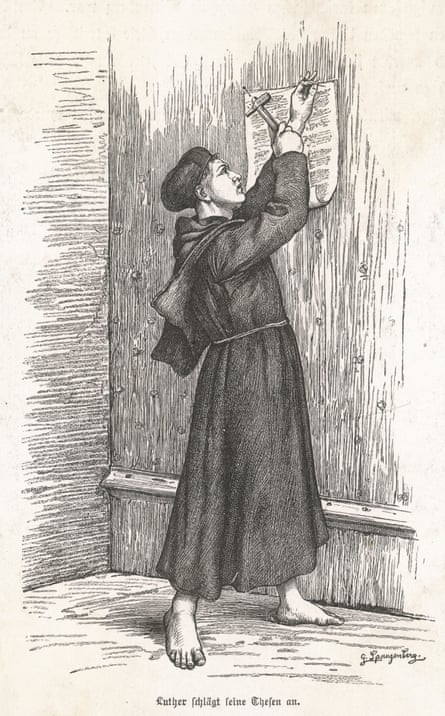

It would be a tough assignment. But take heart: there once was a man who had similar doubts about the dominant power of his time. His name was Martin Luther and 500 years ago on Tuesday he pinned a long screed on to the church door in Wittenberg, which was then a small and relatively obscure town in Saxony. The screed contained a list of 95 “theses” challenging the theology (and therefore the authority) of the then all-powerful Catholic church. This rebellious stunt by an obscure monk must have seemed at the time like a flea bite on an elephant. But it was the event that triggered a revolution in religious belief, undermined the authority of the Roman church, unleashed ferocious wars in Europe and shaped the world in which most of us (at least in the west) grew up. Some flea bite.

In posting his theses Luther was conforming to an established tradition of scholastic discourse. A “thesis”, in this sense, is a succinctly expressed proposition put forward as the starting point for a discussion. What made Luther’s theses really provocative, though, was that they represented a refutation of both the theology and the business model of the Catholic church. In those days, challenging either would not have been a good career move for an Augustinian monk. Challenging both was suicidal.

To understand the significance of this, some theological background helps. A central part of Catholic theology revolved around sin and the consequences thereof. Sins were divided into three grades – original, venial and mortal. The first was what you were born with (because the default setting for humans was “flawed”) and was absolved by baptism. The second category consisted of peccadillos. The third – mortal – were grievous sins.

The church had established an elaborate machine for enabling its members to deal with their moral transgressions. They could confess them to a priest and receive absolution on condition that they did a prescribed penance. But for a medieval Catholic, the visceral fear was of dying with an unconfessed – and therefore unabsolved – mortal sin on your record. In that case, you went to hell for eternity, tortured by perennial fire and all the horrors imagined by Hieronymous Bosch.

If you died with just unabsolved venial sins, however, then you did time in an intermediate prison called purgatory until you were eventually discharged and passed on to paradise. Being in purgatory was obviously better than roasting at gas mark six, and your place in heaven was ultimately guaranteed. But if you could minimise your time in the holding area then you would.

Into this market opportunity stepped the Roman church with an ingenious product called an indulgence. This was like a voucher that gave you a reduction in your purgatorial stay. Initially, you could get an indulgence in return for an act of genuine penitence – following the confessional model – or for visiting a holy relic. But there came a moment (in 1476) when Pope Sixtus IV announced that indulgences could be purchased on behalf of another person – say a deceased relative who was assumed to be suffering in purgatory, and therefore lying beyond the reach of confession and absolution. In a continent of credulous and devout believers, this turned indulgences into a very big business. And, as with the US sub-prime mortgage market pre-2007, it got out of hand. By 1517, as Luther saw it, indulgences had become a racket in which a crass financial transaction substituted for the serious duty of real repentance. A couplet coined by a particularly enthusiastic indulgence-hawker captured this crudity nicely:

As soon as a coin in the coffer rings,

The soul from purgatory springs.

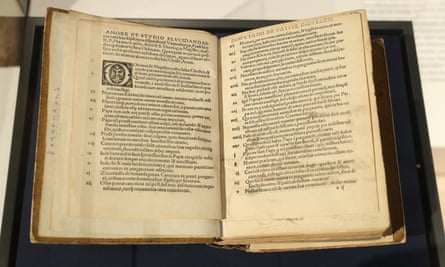

The audacity of Luther’s 95 Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences came from the fact that in attacking the theology underpinning the doctrine of purgatory they were also undermining the business model built upon it. In two consecutive theses, 20 and 21, for example, Luther set about attacking the very essence of papal authority. “When he [the pope] uses the words plenary [ie total] remission of all penalties,” Luther wrote, “he does not actually mean ‘all penalties’, but only those imposed by himself.” Therefore, continues thesis 21, “those indulgence preachers are in error who say that a man is absolved from every penalty and saved by papal indulgences.”

This might not look like much to a modern reader, unfamiliar with the intricacies of 16th-century Catholicism, but it was the equivalent of calling the pope a liar. And in the Europe of 1517, that was fighting talk. People had been burned at the stake for less. In the ordinary course of events, the church would have squashed such a turbulent friar as one would a mosquito. All it would have required was a letter to his religious superior, followed by a kangaroo court in Rome, and that would be that.

But it didn’t happen. Instead, Luther escaped death, survived excommunication and went on to light the fire that consumed Christendom. How come? Historians cite two main reasons. The first is that Luther was lucky in that Frederick the Wise – the local bigwig who was one of the seven electors of the Holy Roman Emperor – protected him and indeed saved his life (protection that was continued by Frederick’s heirs and successors). The second is the printing press, which is what enabled Luther to “go viral”, as modern parlance has it.

Of course we’ve known for eons about the role of print in the Reformation. But it’s especially interesting to look back at the story in the light of what has happened to our own media ecosystem in the past few years. After all, we have lived through political earthquakes that were fuelled at least in part by new media, and we find ourselves contemplating what has happened with the same kind of “informed bewilderment” that must have afflicted Pope Leo X as he watched his pestilential priest become the most famous man in Germany.

What happened, in a nutshell, is that Luther understood the significance and utility of the new communication technology better than his adversaries. In that sense, he reminds me of Donald Trump, who sussed how to use Twitter and exploit the 24-hour news cycle better than anyone else. But whereas Trump contributed nothing to the communications technology that he exploited, Luther did.

His understanding of the new media ecosystem brought about by print has been expertly explored by the Reformation historian Andrew Pettegree in a brilliant book, Brand Luther: 1517, Printing, and the Making of the Reformation (Penguin, 2015). Unlike most scholars of his time, Luther was both interested in and knowledgable about the technology of printing; he knew the economics of the business, cared about the aesthetics and presentation of books and understood the importance of what we would now call building a brand.

He knew, for example, that his message would only spread if he gave printers texts that would be economical to print and easy to sell – unlike conventional scholarly books in the early decades of printing. Because paper was expensive, printing a standard scholarly tome required capital resources for buying and storing the necessary reams of paper. And because there was no developed market for distributing and marketing the result, many printers went bankrupt – which is why most printing and publishing was concentrated in large towns with established universities where at least some of the necessary infrastructure existed.

Although the original 95 theses were in Latin, as were most theological books of the period, Luther decided that he would write in German. In doing so he immediately expanded his potential market by orders of magnitude. He also developed a literary style that was, as Pettegree observes, “lucid, readable and to the point”. But his masterstroke was in enabling printers to make money by publishing his works. Because paper was expensive, he channelled his output into extended pamphlets that could be printed on one or two sheets of paper, suitably folded into eight or 16 pages at most.

The strategy worked. Within five years of posting his theses he was Europe’s most published author. A printed sermon or a commentary by Luther was a surefire seller, and appealingly inexpensive to produce. The nascent printing industry was quick to respond: Wittenberg, which had a solitary shambolic printer when Luther began, was soon home to a handful of presses, including one run by Germany’s most accomplished publisher, Moritz Goltz. Luther, proactive to a fault, took care to spread his work among all of these new publishing houses and was, Pettegree observes, “sufficiently popular to put bread on the table of publishers throughout Germany”. By the time Luther died in 1546, nearly 30 years after posting the 95 theses, this small town in Saxony had a publishing output that matched that of Germany’s biggest cities.

Luther was clearly a remarkable, complex individual – charismatic, divisive, inspiring, intense, gifted, musical, courageous, devout and lucky. He also had a very unattractive side – as seen most starkly in the misogyny and ferocious antisemitism with which his works are peppered. But I’ve always been fascinated by him, and as the 500th anniversary loomed and Trump rose to power on the back of our new media ecosystem, I fell to pondering whether there are lessons to be learned from the 95 theses and their astonishing aftermath.

One thing above all stands out from those theses. It is that if one is going to challenge an established power, then one needs to attack it on two fronts – its ideology (which in Luther’s time was its theology), and its business model. And the challenge should be articulated in a format that is appropriate to its time. Which led me to think about an analogous strategy in understanding digital technology and addressing the problems posed by the tech corporations that are now running amok in our networked world.

These are subjects that I’ve been thinking and writing about for decades – in two books, a weekly Observer column, innumerable seminars and lectures and a couple of academic research projects. Many years ago I wrote a history of the internet, motivated partly by annoyance at the ignorant condescension with which it was then viewed by the political and journalistic establishments of the time. “Don’t you think, dear boy,” said one grandee to me in the early 1990s, “that this internet thingy is just the citizens band [CB] radio de nos jours?”

“You poor sap,” I remember thinking, “you have no idea what’s coming down the track.”

Twenty-five years on, I now describe myself as a recovering utopian. When the internet first appeared I was dazzled by its empowering, enlightening, democratising potential. It’s difficult to imagine today the utopian visions that it conjured up in those of us who understood the technology and had access to it. We really thought that it would change the world, slipping the surly bonds of older power structures and bringing about a more open, democratic, networked future.

We were right about one thing, though: it did change the world, but not in the ways we expected. The old power structures woke up, reasserted themselves and got the technology under control. A new generation of corporate giants emerged, and came to wield enormous power. We watched as millions – and later billions – of people happily surrendered their personal data and online trails to be monetised by these companies. We grimaced as the people whose creativity we thought would be liberated instead turned the network into billion-channel TV and morphed into a new generation of couch-potatoes. We saw governments that had initially been caught napping by the internet build the most comprehensive surveillance machine in human history. And we wondered why so few of our fellow citizens seemed to be alarmed by the implications of all this – why the world was apparently sleepwalking into a nightmare. Why can’t people see what’s happening? And what would it take to make them care about it?

Why not, I thought, compose 95 theses about what has happened to our world, and post them not on a church door but on a website? Its URL is 95theses.co.uk and it will go live on 31 October, the morning of the anniversary. The format is simple: each thesis is a proposition about the tech world and the ecosystem it has spawned, followed by a brief discussion and recommendations for further reading. The website will be followed in due course by an ebook and – who knows? – perhaps eventually by a printed book. But at its heart is Luther’s great idea – that a thesis is the beginning, not the end, of an argument.

John Naughton’s theses

No 19: The technical is political

This thesis challenges the contemporary assertion of the tech industry that it stands apart from the political system in which it exists and thrives. This delusion has deep roots – for example in the fact some of the dominant figures of the 1970s computer industry were influenced by 1960s “counterculture”, which was suspicious of, and hostile to, the US political and corporate system that had enmeshed the country in the Vietnam war. It found its wildest expression in John Perry Barlow’s 1996 Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.

The idea that the tech industry exists, somehow, “outside” of society was always misconceived, even when the industry was in its infancy. After all, it was built on the back of massive public investment in defence electronics, networking and research conducted in corporate laboratories such as Bell Labs or consultancies such as BBN. But in an era where it’s clear that Google and Facebook have, unintentionally or otherwise, been influencing democratic politics and elections, it is positively delusional. We have reached the point where almost every “technological” issue posed by the five giant tech companies is also a political problem requiring political and possibly legislative responses. The technical has become political.

No 92: Facebook is many things, but a “community” it ain’t

One of the favourite phrases of Mark Zuckerberg is “the Facebook community”. Facebook is many things, but a community it is not. It’s a social network, which is something quite different. In a social network (online or off), people are connected by pre-existing personal relationships. Communities, on the other hand, are complex social systems because they consist of people from different walks of life who may have no personal connections at all. A good example is the English village where I live. I am friends with some villagers, and know my neighbours pretty well. But there are many others in the village whom I don’t know and with whom I may have little in common. But there’s no doubt that they and I are all members of the same community.

Online groups confirm the power of homophily – the tendency of individuals to associate and bond with others of similar ilk. Facebook provides a framework that contains innumerable homophilic groups. But it isn’t a community in any meaningful sense of the world.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion