Gillian Triggs, Australia’s controversial former human rights commissioner has had a personal experience of the dangers of data retention laws.

She was caught out, she reveals in a new report on Digital Rights, when she agreed to provide access to 24 hours of her digital life as part of an experiment at the Melbourne Writers Festival in 2017.

As her emails were put on a screen behind her, the audience tittered.

Her digital indiscretion was a minor one. She had applied for a seniors card.

But Triggs’ experience illustrates a point, made over and over in the Digital Rights Watch state of the nation report: your digital life is easily tracked, mapped, stored and exploited.

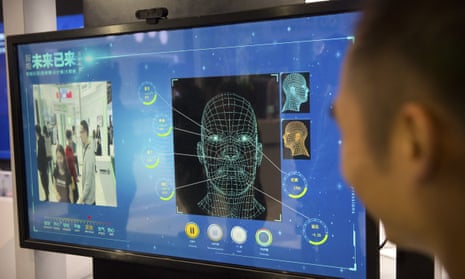

And the tools to more accurately track and match your data to you are about to be greatly enhanced by the use of facial recognition software, making it almost impossible for people to opt out of giving their details any time they are physically present.

The report from Digital Rights Watch, released on Monday, calls for a series of reforms to better protect Australians’ digital rights.

While the revelations by Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning about the scale and reach of surveillance in the US, and the activities of Cambridge Analytica in seeking to manipulate elections have highlighted what is possible, Digital Rights Watch warns this is just “scratching the surface”.

“A much wider, systematic and wilful degradation of our human rights online is happening,” the group’s chairman, Tim Singleton Norton warns.

The report warns that new technologies, such as facial recognition software, will open up new opportunities for advertisers and marketers but also pose significant new risks.

Dr Suelette Dreyfus, from the school of computing at the University of Melbourne, said data about people’s movements and behaviours collected by shopping centres, retailers and advertising companies could be combined with new technologies that included physical biometric identification, mood analysis and behavioural biometrics.

This, she warned, would remove consumers’ ability to not give their details or use a pseudonym when when dealing with an organisation that collects data, like a supermarket. That has the potential to undermine one of the key protections of the Privacy Act – the right not to give your details.

Dreyfus also said the biometric analysis technology now used for security was being repurposed to monitor the mood of individuals and their responses to advertising. It could also be used by employers to monitor the mood of employees.

“This technology is being sold and implemented despite the clear privacy and ethical issues with its implementation and the questionable value of the measurement itself,” she said.

Data Rights Watch is urging the development of an opt-out register for people who do not want their movement data used for commercial purposes. It is calling for a compulsory register of entities that collect behavioural biometric data.

The report also warns that Australia’s laws have failed to protect human rights.

“Upholding digital rights requires us to find the balance between the opportunity the internet provides us to live better, brighter and more interconnected lives, and the threat, posed by trolls, corporations and government,” Norton said. He is calling for a more nuanced debate.

The report highlights a number of concerns about Australian law and calls for the immediate scrapping of the law that requires telecommunications companies to retain their customers’ metadata for two years.

The report says that current regime effectively allows law enforcement bodies to watch everybody all of the time without them knowing. Warrants are not required except in the case of accessing journalist’s metadata, presumably to protect sources.

It notes there are reports of some organisations, including government departments intentionally circumventing privacy protections within the legislation in order to gain access to data they are not authorised to have.

It is also calling for new laws that respects and uphold the right to digital privacy and to data protection. It wants the government to create a similar body to the European Data Protection to monitor privacy protections.

And the group proposes a “right to disconnect”, which would prevent employers using digital tools to encroach on statutory rest breaks or holidays of their workers.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion