History of Texts and Popular Media

As someone who studies the history of texts, I try to avoid commenting on the portrayal of textual history or librarianship in popular media (don’t get me started on Jocasta Nu in Attack of the Clones) in casual settings. What good does it do to point out that a manuscript’s hand doesn’t match the era, or that a particular text wouldn’t be in the vernacular, or that rare books should NEVER be perused while consuming an apple or burning incense? Probably not much, though you better believe textual historians have these conversations all the time!

This is why I am delighted when they get it right. I’ve spent some time over the past few weeks playing Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey (ACO), an epic adventure game set in the year 431 BCE. In the game, you play as a mercenary (in my case, Kassandra) navigating the political and military landscape of Greece during the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. The map is seemingly endless, the vistas beautiful, and my time sailing and attacking pirate ships has almost made me forget about the COVID-19 quarantine and my cancelled travel.

From the beginning of the game you are encouraged to find something referred to as Ainigmata Ostraka – these are stone tablets hidden in various locations that contain riddles that guide you to “engravings” that level up your weapons. (Here is a brief clip of me finding one.) Huzzah, a real text technology from the time, and — I am happy to report — ostraka make another appearance crucial to the main mission of the game that is true to their historical importance (more on this later).

What are Ostraka?

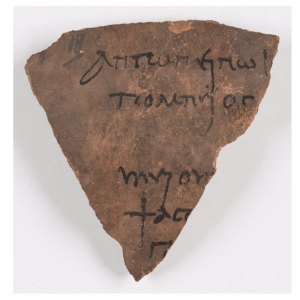

The word ostraka (plural) or ostrakon (singular) refers to a piece of pottery, usually broken off from a larger vessel (a potsherd), that has been reused as a writing surface. Ostraka were plentiful in the ancient world and were typically inscribed in Greek, Latin, Arabic, or Hieratic script (Ancient Egyptian). While papyrus was also available, it was expensive and usually reserved for documents that needed to last; ostraka recorded more ephemeral notes, letters, and (as you’ll soon see) ballots.

FSU Special Collections and Archives have a collection of 32 ostraka from circa 150 CE, much later than the time period of the game, but they match physical descriptions of ostraka across these centuries. Here’s how Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey’s portrayal of ostraka aligns with the historical record:

Almost, but Not Quite…

Most ostraka were small.

When my character discovers ostraka, they are usually all about the same size. They are very regular in shape, rectangular, and about the length of Kassandra’s forearm. Ostraka of that size have existed in history, but they were exceptional and, it seems, rare. Based on real ostraka that survive, it appears that a majority were very small pieces, about the size of one’s hand or even smaller, and their shapes are extremely irregular.

Ostraka were not usually flat.

The ostraka stored under “Documents” in your ACO inventory appear to be flat. Usually, real ostraka give an indication of the shape of the pot or clay item that the shard was originally a part of. They will frequently have a curve to them; I’ve often thought that the shape might rather conveniently conform to the writer’s leg during the inscription process.

Ostraka were usually written in ink or scratched into paint, rather than carved.

We don’t get to see very close, detailed depictions of the ostraka in ACO, but they do appear to be engraved, almost like a cuneiform tablet, rather than written. Writers sometimes used the same tools they used for writing on papyrus — a small brush or reed pen — to compose in ink on their ostrakon. If the pottery was painted, or had a dark glaze on it, the writing could be etched into the painted surface – the effect looked less like a stone tablet and more like words scratched into paint, like bathroom stall graffiti.

Absolutely Correct

Ostraka were plentiful.

Consider them the post-it note of the ancient world! Ostraka were used for many different purposes. Pottery was the primary means of storing, preserving, and transporting goods, so shards of pottery were nearly unlimited in supply.

Ostraka are found in strange places.

Archaeologists find groupings of ostraka in places you might not expect: in trash heaps, at the bottom of wells or fountains, under the foundations of houses. This relates to the purposes they usually served. Either they were ephemeral notes that were discarded, or they were inscribed as a means of imbuing some sort of metaphysical power into the description, and tossed into a well or buried under a house to complete the ritual. FSU Special Collections and Archives’ ostraka were discovered in an archaeological dig of a trash heap next to a Roman military outpost in Edfu, Egypt.

Ostraka can vary in color.

I was happy to see that the ACO designers created ostraka that come in a variety of colors. As ostraka come from broken pottery that would have been crafted in various places, the components of the clay would differ according to geography. Additionally, some pottery was painted or treated, and would have color differentiation accordingly.

Ostraka can tell a full story.

While most ostraka contain very brief inscriptions, some give us a glimpse into the lives of the people who wrote them. We even have a pretty explicit love poem. Here’s a different example that illustrates this in FSU’s ostraka collection:

“Sentis to Proclus her brother, greeting. You did well, brother, in giving the two kolophoia to Anchoubis; also write to me about the passage-money and I will send it to you at once. I did not send you meat, brother, so that I might not bid farewell to you. Therefore I ask you, sir, show respect (?) to me and come this the Ethiopoan, Let us be happy. Farewell. (At the side) Do not do otherwise, then, but if you love me come. Let us be happy.”

Ostraka were used to vote people out of Athenian society, and the etymological source for the word “ostracism.”

You might not know that the word “ostracism” derives from a practice in fifth-century Athens that relied upon ostraka: ostrakismos. The process is succinctly described here:

The procedure was as follows: Every winter, the full assembly of Athenian citizens (i.e. free adult males) was asked whether it wanted to hold an ostrakismos. If a majority – not counting less than 6,000 – agreed, the event was held two months later. For this purpose, a large area within the Agora was corralled off. Every citizen could enter. On doing so, he handed a potsherd (ostrakon) to an official, inscribed with the name of the individual he wished to see ostracised, further identified by his father’s name and the deme (district) he came from. To prevent multiple votes, the citizens had to wait within until the vote was complete. The sherds were then counted and the person most frequently chosen, again subject to a minimum of 6,000 votes, was ostracised.

The ostracised citizen was given ten days to settle his affairs and leave Athens. His citizenship was not affected, nor was his property touched, and he retained access to its proceeds. He was not to return to the city for ten years – on penalty of death – unless a public vote recalled him at an earlier date. Ostracism was not considered per se dishonourable; status and rights were fully reinstated on return. (https://www.petersommer.com/blog/archaeology-history/ostraka)

In Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, Kassandra is introduced to this practice when she is asked to sneak into the location where the ostraka are being counted and rig the votes by switching out the ostraka with fake ones. In this case, the ostraka appear to be small, dark round pieces, which perfectly matches the piece of pottery that was typically used in the process – the disc-shaped bottom of a stemmed drinking vessel.

Many thanks to Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, for the excellent portrayal of ostraka as a historical text technology. One caveat: I’m currently only at level 24 in the game, so it’s possible that ostraka make more appearances that would change my perspective. If that’s the case, please let me know!

And as always, FSU Special Collections and Archives materials are open to the public. While our reading rooms are currently closed due to the pandemic, our ostraka collections (and other awesome pre-print materials) are available in our digital library, DigiNole. I encourage you to browse them at your leisure!