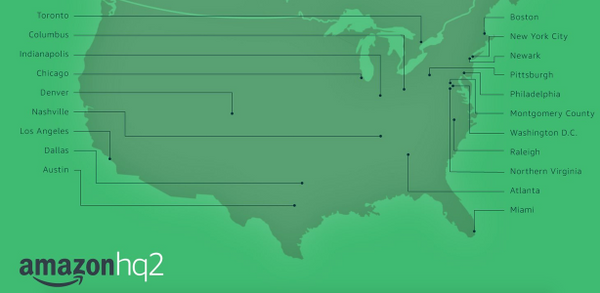

Regardless of what camp you find yourself in on the topic of Amazon’s HQ2 courtship with North American cities, the process has triggered open record requests and questions about the degree to which cities are required to disclose the documentation of their overtures to the corporate giant.

This is especially true in Pittsburgh, where inclusion of the region’s bid, titled PGHQ2, as one of 20 finalist cities led to renewed demand for the full proposal to be released via the state’s open records law. Why is this important? Many cities have offered significant tax and civic incentives to sway Amazon’s interest. With promised results of $5 billion in economic investment and the creation of 50,000 jobs, an argument can be made that it is in the public interest to know how elected officials believe HQ2 will influence the social, political, and economic fiber of their region.

These desire for details have manifested themselves in open records requests throughout many candidate cities, to varying degrees of success. Pennsylvania’s mechanism for open records requests, the Right-to-Know Law, was signed into law in 2008 and is facilitated by the state’s Office of Open Records. Like many open records laws, all records are presumed to be public and are deemed “open” unless one of several exceptions bars their disclosure. Thus, the burden is on the government agency to argue why certain records, for instance a proposal with wide-ranging public impact, should not be made publicly available.

So what’s happening in the Steel City? Like hundreds of other cities across North America Pittsburgh submitted its bid in October 2017, the details of which were not publicly disclosed. PGHQ2, led by elected city and county officials, first cited a confidentially agreement with Amazon. The reasoning for secrecy soon shifted to “protecting a competitive advantage.” Right-to-Know requests for the proposal were refused. Requests for secondary records (letters, emails, notes) pertaining to the process, not the proposal itself, were met with half hearted gestures. The City initially stated those weren’t public either; the county responded that “the records do not exist.” Eventually these secondary requests were fulfilled through state intervention (Harrisburg itself is a big proponent of Pittsburgh’s bid).

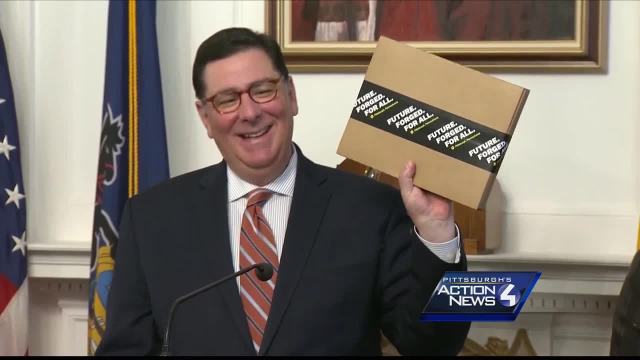

But what of the PGHQ2 proposal? As is often the case with open records requests, persistence pays off. Fast forward two months to January 24, when news broke that Pennsylvania’s Office of Open Records issued a ruling on a Right-to-Know request filed by local WTAE reporters ordering Allegheny County and the City of Pittsburgh to make the full PGHQ2 proposal and corresponding documentation public within 30 days. In a coincidental twist, both entities have 30 days to appeal, the same period one has to return unopened items to Amazon. If delivered, there’s no doubt Pittsburghers will open this proposal package.

The jury is still out on whether or not it’s truly in the region’s best interest that the PGHQ2 push is successful. With revived economic sectors, oft-touted cultural amenities, regional charm, and room to grow, Pittsburgh’s case is compelling. But the records and documents supporting that case shouldn’t be kept from the very citizens that make Pittsburgh so alluring. Open records laws, like Pennsylvania’s, are meant to serve the public good and promote transparent and accountable government. If Pittsburgh officials baited the PGHQ2 hook with tax incentives, public domain authority, or questionable civic inducements, the citizens of Southwest Pennsylvania certainly have a Right-to-Know.