The following is a RMS guest post by Maarja Krusten, a retired Federal government historian who worked on records, archives, and historical research assignments and served for 14 years as an archivist in NARA’s Office of Presidential Libraries.

Margaret M. H. Finch once said that working with permanently valuable Federal records made the people described in them “almost become living people.” Who was Finch? And what provides context for her own story? Records!

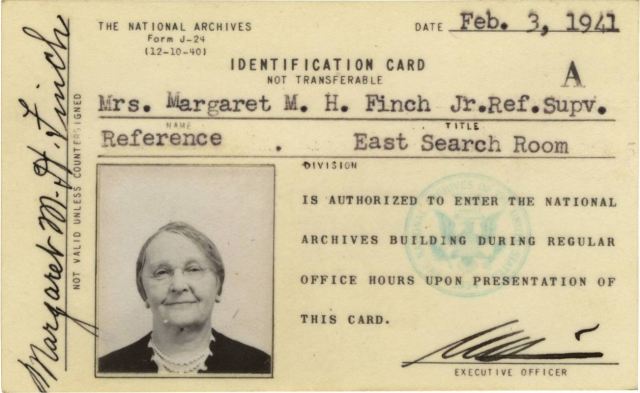

After the death of her husband in 1918 during the influenza epidemic at the end of World War I, M. M. H Finch joined the Pension Bureau. She became a branch chief and top expert in the pension records of the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. In 1940, the Pension Bureau transferred the records to the National Archives.

Finch transferred to the National Archives at the time the pension records were accessioned and worked there until her retirement in 1949. In 2015, the staff of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) shared Finch’s story on Social Media:

“She continued to help researchers locate pension files but also gave numerous talks about researching in the records. . . .In an interview conducted upon her retirement, she explained the files made the men who served ‘almost become living people, and their descriptions of battles in which they fought are so real you feel like you’ve been an actual participator.’”

The research I’ve done on the construction of office buildings in Washington, DC. enhances and provides context for Finch’s story. The National Archives holds textual and photographic records from the Commission of Fine Arts (Record Group 66) and the Public Buildings Service (RG 121). These include a wonderful photo taken in 1940 of the Pension Building where Finch once worked. I tweeted the photo in 2017—note my inclusion of the source information!

We can use such stories to show why records matter. Records managers ensure the proper disposition of records, including the retention of those that have historical value. But information professionals know that the people they serve in academic, corporate, government, and other offices are busy with day-to-day mission work.

Where do employees hear about what is happening with records created outside their employing organizations? Sometimes, it’s in a negative context—a data hack, the leak of internal documents, controversies over who said what and when. But there are positive examples out there, as well. And not just in the history books some of us love to read.

I’ve been thinking about that in the context of working many Education and Public Programs Division events at the National Archives and Records Administration. Some relate to temporary displays, others to long-term exhibits, such as “Remembering Vietnam,” which ran November 10, 2017 to February 28, 2019.

I met many Vietnam war veterans over the course of the last year as I helped staff programs related to the exhibit. I found seeing veterans reconnect with their past experiences through the records shown in the exhibit and displayed during panel discussions deeply poignant.

Last February I talked to visitors to the National Archives Museum about the Emancipation Proclamation. It’s a fragile document displayed only once a year, at most, and then only for three days. I especially enjoyed the questions from students, one of whom pointed to a faded circle on the last page and asked if someone had set down a cup of coffee!

A great opportunity to talk about conservation—not just the iron-based ink, but why the seal and ribbons at the top of the last page deteriorated over time. And why President Abraham Lincoln signed his full name., not just the A. Lincoln he used in routine documents.

Employees participate in records management training sessions in-person or online. But unless they work as historians, policy analysts, lawyers, or in other knowledge-dependent functions, they may not have time to think about why saving historically valuable records is as important as destroying or deleting ones that only have short-term value.

Sure, they may see news of an important records release by the National Archives. Or they go to see exhibits in archives, museums, historical societies. But they may not think about the insights records preserve about their own places of employment. Let’s help them see that their stories matter, too.

Whether we work in academic, corporate, or governmental settings, we can look for stories about the places where we work. And use them to bring the past to life. By providing interesting historical information about the construction of the buildings in which they work. Or how the employing organization’s workplace evolved over time. And what it took to make change happen.

To connect past and present. And to remind employees that they are part of a valuable through line. One that stretches from those who came before to those who will follow. Preserved for future use by records managers–and those who support them.

Reblogged this on Archival Explorations.