We were delighted to welcome Cherwell School student Jack Evans on a sixth-form work placement here in the archives. One of his assignments was to catalogue a box from the Stuart Piggott archive. Here are his thoughts on what he found:

“Recently I spent a week working at the Institute of Archaeology as work experience. Working through the archives was the most interesting time I spent, as I read through the notes and letters of Stuart Piggott. Piggott was a celebrated archaeologist who had a key focus on prehistory, initially in the British Isles but towards the later years of his career increasingly so in India and Europe as a whole. He began work in 1928, aged 18, and published influential papers and books until his final book in 1989. As a result of the quality of his work, he was often in communication with other celebrated archaeologists, and so his archives are a wealth of information, revealing much about the field as well as those who populated it.

Churn Bell Barrow, Berkshire, 1932: photo Stuart Piggott. (HEIR ID 35356, copyright Institute of Archaeology)

The history of archaeology, that is, the study of archaeologists and their craft, explores two periods of history simultaneously. The ancient history examined through excavated artifacts exists alongside the early modern history of the 20th century in which the archaeologists lived, allowing us to see how cultural and societal norms helped to influence the ways in which we studied our ancient ancestors as the field developed.

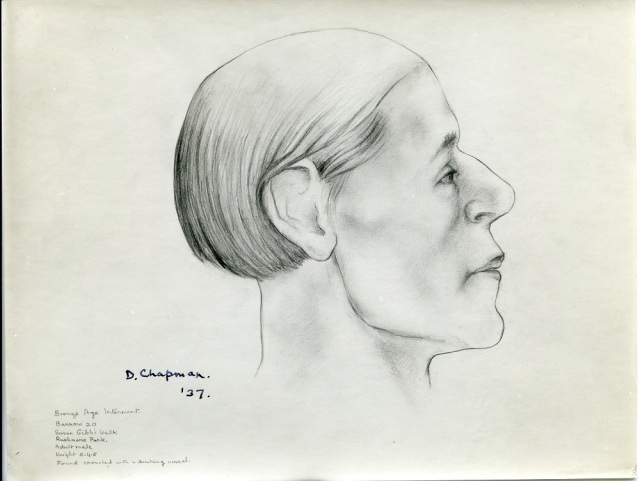

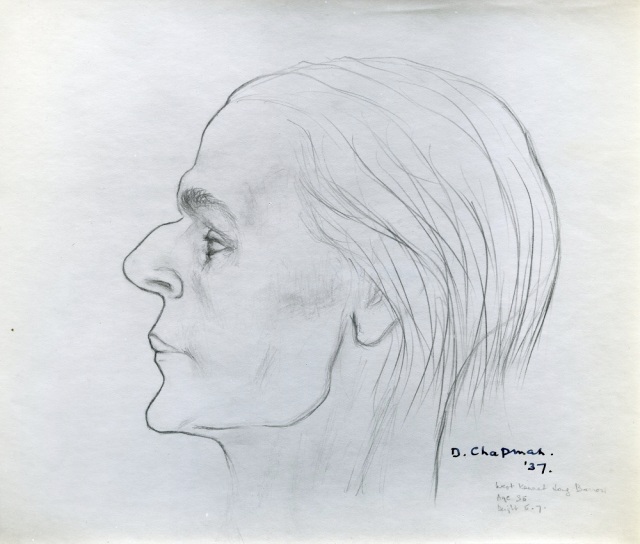

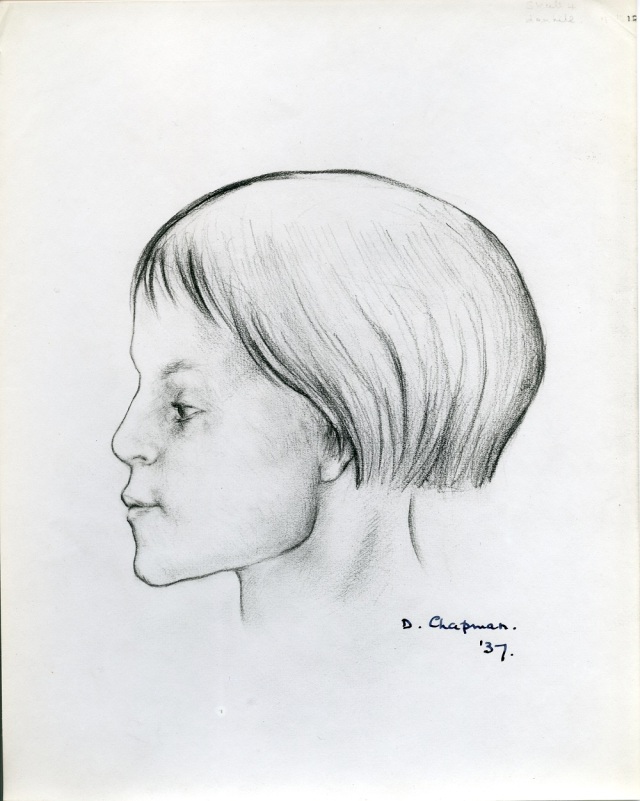

Doris Chapman, whose only online presence is as the wife of Alexander Keiller (a famous archaeologist), demonstrates this in various ways. Chapman was an artist, and Keiller’s third wife. As I worked through Piggott’s archive, organising each item he had decided was important enough to preserve, I came across groundbreaking work she had done in 1937 – a collection of drawings (Piggott Archive Box 52). She used Bronze Age skulls found at sites such as a burial mound at Rushmore Park, Cranborne Chase (excavated by General Pitt Rivers in the 19th century), and Lanhill Barrow, near Chippenham, Wiltshire (excavated by Kieller, Piggott, A.D. Passmore and A. Cave in 1937) to attempt to draw the faces of humans from over four thousand years ago. She used the structural features of the skulls, creating photo-realistic drawings that helped to put a face to the people who lived in these sites, the people who used the weapons and pottery that had been excavated alongside their skeletons.

“Bronze Age Interment. Barrow 20, Susan Gibb’s Walk, Rushmore Park. Adult male, Height 5.4.5” D. Chapman 1937

“West Kennet Long Barrow. Age 35. Height 5.7.” D. Chapman, 1937.

“Skull 4, Lanhill.” D. Chapman, 1937.

At this point in time the study of the face was not without controversy. In archaeology, very few people had made efforts to deduce the appearances of prehistoric peoples (Wikipedia claims that the first to do so was Mikhail Gerasimov in 1964). In wider culture, the study of physiognomy, where personality and traits are determined by examining the face, had become increasingly widespread in Europe. The Nazi party promoted the identification of and the characterisation of ethnic groups based on facial features through their national school curriculum, a policy which aided their dehumanisation of the groups they would later systematically destroy. Doris Chapman’s efforts seem to have come at the wrong time. War broke out in 1939, and as it continued, and the Nazi’s goals became evident, the study of the face became a taboo concept . Nobody would want to carry out work that could be likened to the work of the Nazis, and more accurate visualisations of prehistoric peoples would not be created for decades. Societal pressures had confined the study of the face to a far smaller role following 1937.

Chapman’s work also allows us to see how technology and its availability influences how we see the distant past. When comparing her drawings to modern day reconstructions, such as that of the Jericho Skull in 2017, we can see the drastic differences. The importance of archives and their organisation can be seen here therefore, as it allows us to see how archaeologists and historians reached their conclusions with the means available to them. As technology improves, new conclusions can be drawn. This does not invalidate the work of the earlier archaeologists, but rather shows that they are key steps towards building the most accurate image and perception of history. It is easy to imagine Chapman’s drawings being used as evidence to determine the character of the people who lived near modern Chippenham, for example, with this knowledge then influencing other conclusions drawn about culture and intelligence. As technology and ideas have improved these conclusions can be altered, improved, moving closer and closer towards a truthful account.

The cover Stuart Piggott’s notes for ‘Neolithic Cultures of the British Isles’. Institute of Archaeology, Oxford, Stuart Piggott Archive, Box 52.

This can even be seen in Piggott’s later work, for example a 1954 book concerning Neolithic cultures in the British Isles was challenged in its chronology by the advent of radiocarbon dating. However, this also teaches us an important lesson about modern day efforts – they are constrained by our own cultural beliefs and modern technology. It is difficult to find any certainties, and it is necessary to remain open to the possibility that new scientific methods and apparatus can provide compelling evidence to change interpretations of the past.

Finally, the drawings show us the struggle which women have faced, especially in archaeology, to have their work recognised and to make a name for themselves. The Oxford University Archaeological Society, established in 1919, did not accept women until 1927, as I discovered when I worked on the OUAS archive. Often women were sidelined by their husbands, despite carrying out much important work themselves. Chapman shows another woman who, despite fascinating work and incredible artistic talent, found herself lost into obscurity. She is Keiller’s wife to most concerned, her work hidden from many. Despite this, we can see even more the injustice of the public, as she was clearly acknowledged in private. An archaeologist with the reputation of Piggott recognised the importance of these drawings, keeping them in his own personal archives. Growing equality today again shows us how perceptions change with culture. Ideas developed by women which may have been ignored out of hand in the past are now considered equally, and this helps to lead to a more balanced view of history – both ancient and not so ancient.”

Jack Evans, The Cherwell School, Oxford, August 2018

Bibliography

Piggott, S. 1954. The Neolithic Cultures of the British Isles: A Study of the Stone-Using Agricultural Communities of Britain in the Second Millenium B.C. Edinburgh University Press

Thank you for bringing to light the archive hidden information, it is well done, I await more of it