As many records managers note, recordkeeping decisions are in the news on a daily basis (with today’s accelerated news cycle, it often feels like an hourly basis!). Our last Resourceful Records Manager interview astutely noted, “As I first assumed RM responsibilities, I sat in on a conference talk by a leader in the field, who cited a news headline on records mismanagement and dissected it with great enthusiasm. As I realized that records implications are everywhere, the massiveness (and potential massiveness) of the profession made an impression on me.”

It’s increasingly clear that one of the major areas of public discontent is around disposition. Disposition is the decision that guides what should happen to records once they have reached the end of their useful value from the records creator’s point of view. Disposition can either take the form of destruction, or transfer to archives. I am enormously sympathetic to concern over this topic – there are very real worries that public records and data will disappear because it does happen – sometimes for normal reasons, sometimes for scary Orwellian reasons. However, not all disposition is created the same, and one of the most valuable things that records managers can communicate to the public is explaining the difference between what’s normal and what’s not normal when it comes to what should be destroyed and what should be saved.

This isn’t something that only records managers and archivists struggle with – our library colleagues navigating the rocky paths of weeding old books and media have their own public relations horror stories. Librarians and archivists know that a collection development policy is there not only to guide collecting decisions, but to protect librarians and archivists from future headaches (in this case, getting saddled with tons of out of scope collections or donations). A collection development policy is also in the public interest – a library or an archive so bogged down by a backlog of unprocessed and out of scope donations doesn’t serve the general public well at all.

I think of records retention schedules – in many institutional archives, the de facto collection development policy – performing a very similar role. You can’t keep everything due to resource constraints, and even if time and money were no object, you still shouldn’t keep everything from a liability perspective. On a hypothetical basis, the general public understands that all records can’t, and shouldn’t be, kept forever in an institutional setting. Where things break down with public understanding are questions of how long to keep those records, and what should happen to them after they are no longer actively needed.

This was vividly illustrated during some recent research I’ve undertaken on regulatory failures concerning hydraulic fracturing. The short version is that fracking technology and proliferation is far ahead of existing oil and gas regulations. The current regulatory environment cannot keep up with fracking’s environmental impacts, and failures of recordkeeping are a prominent part of larger regulatory failures. Many groups have been filing open records requests to try to understand the impacts of fracking on rural land and water. The Pittsburgh-based investigative reporters of Public Herald has done enormous work in this area, scanning citizen complaint records from Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection, and making them available through a public files website, and mapping the complaints. Many of these complaints trigger subsequent investigations into whether fracking has resulted in an impact on local water supplies. In other words, a “positive determination of impact” would mean that the Department of Environmental Protection found that fracking affected water supplies.

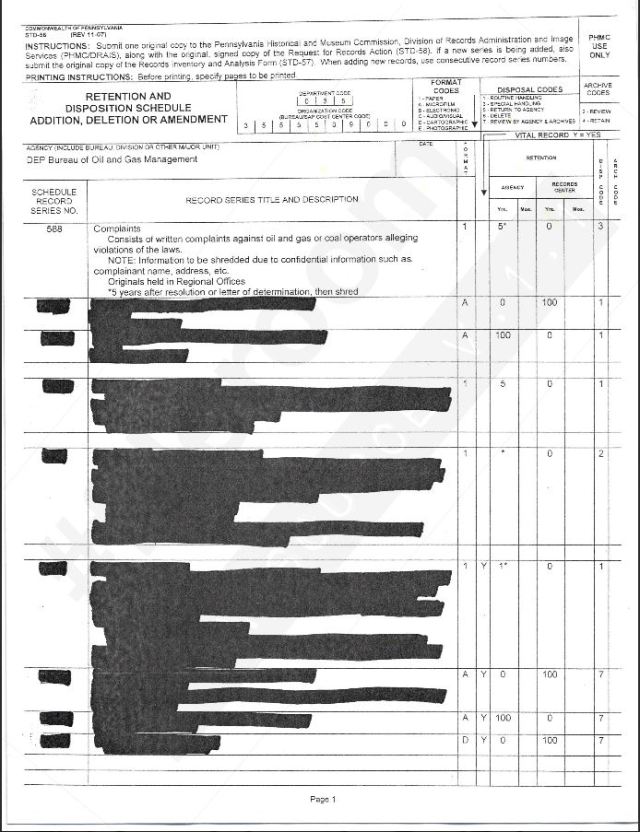

As much as I admire the work of the Public Herald, I strongly object to one of their assertions about a very normal recordkeeping issue. In their article claiming that the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection systematically cooks the books, they laid out nine different methods to substantiate their argument. Some of the recordkeeping practices are indeed serious cause for alarm, but the final one (“DEP Retention Policy for complaint records says complaints are to be kept on file for five years, “then shred.””) struck me as a complete misunderstanding of retention scheduling. Scheduling records for destruction is not a method for manipulating records, and it’s disingenuous to claim otherwise.

The Public Herald wrote the following:

Around month twenty-eight of this investigation, sitting down to scan the last remaining complaint files, a paper with everything blacked out except one paragraph was left on Public Herald’s file review desk by a veteran PA Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) employee. It read “DEP retention policy.” In a paragraph about “Complaints,” the document revealed that the Department should only hold complaint records for five years after resolution – “then shred.”Initially, Public Herald figured these records would be kept on microfiche or a digital PDF and that shredding them would only ensure space within the records office. But, after careful questioning with an employee who’s been with the agency for decades, the staff person revealed that only those records which could be considered “useful” would be kept on record at all, turned into microfilm, and “useful” meant only those listed in DEP’s 260 positive determinations. What shocked us even more is that, according to this whistleblower, there is no review committee in place to sift through the “non-impact” complaint records before they are shredded.

The Public Herald rightfully raises important and compelling questions about how DEP assesses the question of fracking’s impact. But only part of the retention schedule is posted – the remainder is redacted. Without having the full context of the retention schedule, we do not know what other information is kept for say, 100 years (as one of the redacted record groups appears to be), and it very well may be that information otherwise in the public interest is kept for much longer. I tried to do a quick search for the full schedule online – although I could not easily find it (one of my biggest pet peeves common to state agencies – for some reason, I find it easier to obtain municipal and federal agency records schedules), one could almost certainly obtain an unredacted version of it by filing a Pennsylvania Right to Know request.

Perhaps this is the first time Public Herald has encountered a retention schedule, but the presentation of this as a shady and strange document is truly unfortunate. Furthermore, the write-up demonstrates how little the public understands about why records are scheduled the way they are – which is that the vast majority of retention decisions begin, and often end with, “How long must we keep these records to fulfill legal obligations?” Simply put, what is to be gained by maintaining complaint records for more than 5 years, given that most local, state, and federal agencies can barely keep up with managing records as they are currently scheduled? Proposals to retain records even longer would have to make a very compelling reason for why.

Many of the applicable statutes of limitations associated with potential liability brought by complaints would fall within 5 years, so a 5 year retention period for both impact and non-impact determination records doesn’t seem abnormal. Furthermore, the suggestion that a review committee should determine the final disposition of individual records is a recipe for disaster. Public comment absolutely can and should inform the broad formulation of retention scheduling decisions – for example, if members of the public could make a compelling argument for retaining the complaint records more than 5 years, that is something that should be seriously considered and perhaps incorporated into retention policies. But a committee to review the final disposition outcome for individual complaint case files is not realistic, and would almost certainly result in far more political bias. Who would be on the review committee? How would they document their decisions? How fast would they be expected to work? Witness how slow and controversial federal records declassification is if you want a glimpse of what individual-record-determination-decision-by-committee would almost certainly look like in practice.

Bottom line: as many archivists have pointed out, there is almost nothing that is neutral about the world of records and archives. Many records retention scheduling decisions are areas that significantly misunderstood by the general public. It would behoove more records managers to talk openly and transparently about why and how we schedule records the way we do. Others may disagree with our decisions, but at least the process will be clearer to those encountering records retention schedules for the first time.

Update: At their request, this post has been updated to more accurately identify the Public Herald as investigative reporters.

I’ve been working with a small county archive for some of my MLIS classes and the thought of having to go through the contents of a SMALL archive file-by-file is mind-boggling, let alone a state government department!

Dear Eira,

As one of the authors of the report you critique here, I must weigh in.

After more than three years of file reviews at PA DEP, we’ve seen many types of documents that have been kept for decades, whether on paper, CD, or microfiche, after their official use is over, i.e. the drilling logs of wells that have been plugged and abandoned for years.

Our contention is that citizen complaints, which document impacts reported by citizens, are curiously, according to our source at DEP who slipped us the retention policy, discarded after five years during what is nothing short of an experimental extraction process that will last decades.

You fail to mention the culture of secrecy surrounding these particular records, which we also discussed in our report. These records were originally withheld from Public Herald and other organizations as “confidential” so as not to “cause alarm” as one DEP attorney informed me.

Why is a record so important it is held as “confidential” – and one so crucial to the study of health and environmental impacts related to fracking – being discarded after five years?

After pushing DEP to disclose under the Right-to-Know Law, which clearly states that records are to be redacted, not withheld, we were able to access thousands and thousands of these records over several years. But none of them were older than 2007, despite the fact that fracking kicked off in 2004, and oil and gas operations have been managed by DEP for decades.

That’s when our source revealed the retention policy.

Because DEP had never publicly disclosed these records (let alone aggregated or analyzed them for any kind of report on public or environmental safety) the public, the scientific community we work with, and many others were shocked that over 9,400 complaints had been received by DEP since 2007.

Why are these records not scheduled to be stored in another format once their “official use” is over, like other documents that have even less significant information regarding public safety?

We know why – we live here. We’ve investigated “why” for over six years. Your judgement that our report is somehow “disingenuous” tells me you do not understand the historical and cultural circumstances surrounding the disclosure of public health and safety data related to fracking operations.

I encourage you to reserve future judgements of this kind to matters that you fully comprehend.

Sincerely,

Melissa Troutman

Executive Director, PublicHerald.org

Eira, thanks for your insights into the complexities of records management and for your efforts to communicate these complexities beyond our profession. And thanks as well to Melissa Troutman, Josh Pribanic, and Public Herald for continuing to fight tirelessly for us Pennsylvanians.