And it came to pass that Brad was preparing materials for records management training sessions, as one does;

And the frustration with the records management practices put in place by his predecessor did boil over.

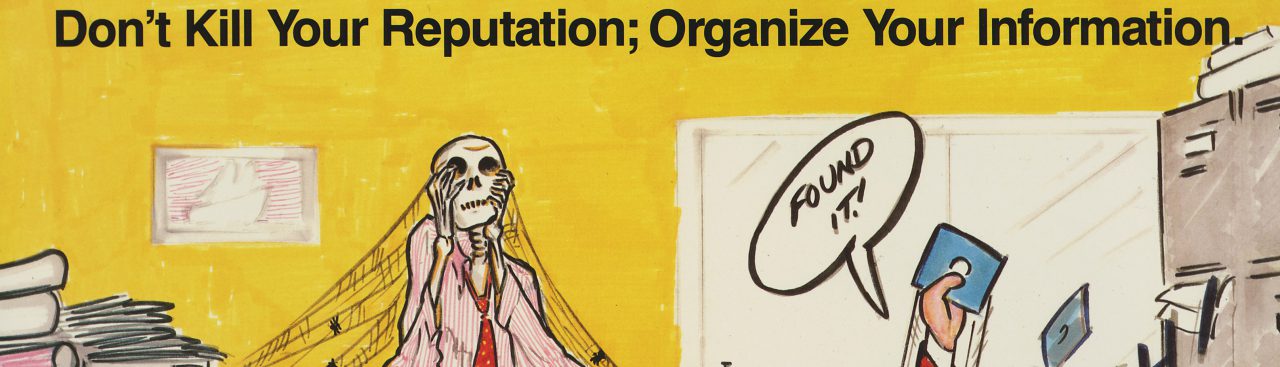

Then did Brad throw together a quick-and-dirty records management graphic, and he shared it on Twitter for a lark.

Lo! That graphic became Brad’s most RT’ed Records Management-related post ever, for Brad hath toucheth a nerve.

…Enough of that. Anyway, I put this together to deal with the new type of decentralization in place at the City of Milwaukee, to wit the records

coordinator network. On the one hand, having dedicated records people in departments is nice and cuts down on your workflow… but the records management experience of these folks is, shall we say, varied, as is their control of the schedules their department may already have in place. As a result, my big records retention project for the first year or so here is eliminating the duplicate, obsolete, and superseded schedules in our database, of which there are 4500, give or take a few dozen. So, that’s a thing.

In any case, due to the unforeseen popularity of the 10 RM commandments, Eira asked me to go through them in a bit more detail. After all, these are Milwaukee-specific, but they speak to some very basic records management principles and best practices. So with that, away we go:

I. THOU SHALT have a records schedule for every type of record created or used by your office.

This is the basic point of retention scheduling—you’re only going to get a complete picture of your records ecosystem if you have all of your records scheduled, because that’s going to tell you how the various series work together. My frustration here has been departments saying “well, we keep these forever so we don’t need a schedule, right?” Wrong. A schedule is still useful for permanent records because it provides business continuity—the rest of your office sees what records are in the series, what they’re used for, and that they even ARE permanent in the first place.

II. THOU SHALT NOT create schedules for non-official copies of records, unless those copies have special destruction requirements.

Seems pretty obvious to us as information professionals, but I cannot count the number of schedules in the database that are pretty obviously for copies of the official record, held by the official office. Given the ease in which copies, especially electronic copies, proliferate, the idea of the “non-record”, and the fact that you can destroy non-records when no longer useful in most cases, is critical. (There is a line of thought that the record/non-record distinction is obsolete; I don’t see it. You’re still looking for the record used to document the actual business transaction, and the fact that other copies can still be discovered is all the better reason to get rid of the non-record copies sooner.)

III. THOU SHALT NOT create records schedules before confirming that a schedule for that series (office-specific or global) does not exist.

Violation of this Commandment is why several records series in my database have 3 different record schedule numbers assigned to them. In most cases, these are created because the previous records schedule couldn’t be found in time for the submission to the WI public records board. This is testament to the need for a) the records manager to organize his/her/their schedules in a way that they will find them again later, and b) the records creator to maintain awareness of the department’s schedules and whether there’s an existing schedule for the documents he/she/they “discovered” in a closet.

Even better, use general schedules. These are easy to make available online, and you don’t have to worry about renewing a million specific schedules (see Commandment 9).

IV. REMEMBER that the existence of a records schedule does not imply a mandate for creation of that record series.

Currently, use of general schedules at the City is opt-in. I’ve already had one discussion where I was told a department didn’t want to opt in to a general schedule because “we don’t create all of the records on that schedule.” The response to this, of course, is, “That’s cool, you’re not obligated to. Records schedules specifically provide guidelines for existing records; they don’t make you create records for the sake of complying with the retention schedule.” This is not as much of a problem with specific schedules, for obvious reasons.

V. HONOR thy retention period; do not destroy records before they have expired.

Again, the whole point of retention periods, to wit giving you a time after which you can defensibly destroy/delete records. If your records creators are destroying records before that, they are doing anything from opening up their institution to spoliation sanctions, to actually breaking state or federal law, in the case of things like Sarbanes-Oxley records and records subject to public records acts.

What I *don’t* usually say in training is that most retention periods are minimums, and that the law doesn’t impose penalties for overretention except as part of the operational consequences of that decision (e.g. data is leaked that would not have been leaked had it been destroyed on time). I’m not going to *lie* if asked point-blank about it, but keeping quiet helps wear down the resolve of many a hoarder.

VI. THOU SHALT NOT create records schedules for the same records in different formats.

There are SO MANY of these in the City schedule database. SO MANY. People who do this are worse than Korach. THESE SCHEDULES ARE WHY WE CAN’T HAVE NICE THINGS.

Well, not really, but they ARE why records creators get confused about retention with multi-format series. “Now, do I keep the paper permanently and scrap the electronic, or do I convert all of it to Microfilm and THEN destroy it, or…” Keep It Simple, Smarty. Record value, being based on content rather than format, should remain constant regardless of format, so why bother with 3 schedules when one will do the job? (Having said that, it may be worth indicating that records from one format may be disposed of once converted to another, e.g. via imaging.)

VII. THOU SHALT group functionally-related records with identical retention periods into as few schedules as possible.

My predecessor *really* liked building records schedules. Unfortunately, this often meant that individual forms or document types would get their own schedules, creating 3-4 schedules where one would have done the job. In general, I have been encouraging departments with a lot of these mini-series, where the various records support the same function and require the same retention period, to supersede the smaller schedules with a broader one that encompasses the whole series vs. individual documents. I was able to eliminate 37 License Division schedules this way—the old way of doing things had individual schedules *for each type of license*, all with the same retention period. Unreal.

VIII. THOU SHALT NOT create records schedules for specific projects or time periods, unless the records are unique and/or scheduled for archival retention.

This is something that would happen from time to time at UWM as well, where departments would submit requests for records schedules for particular projects they were working on. This is, needless to say, not an efficient way to do records scheduling. If you just do one schedule for ALL project files, you cover retention needs for all similar records and don’t have to keep filling out the form every 9 months. The City introduced a new variant that I hadn’t seen before, where one series existed for records before a given date (1846-1900, say), and then a second for records after that date… but again, with the same description and retention period. This is making scheduling harder than it needs to be. Conservation of schedules never hurt anyone.

The one exception to this commandment is that if a series is no longer created, and either of historical value or needing a new records series in order to destroy it, I will reluctantly consent to a project-specific or date-limited series. My overall preference, however, is to go general when possible—and unless you like filling out the same schedule 50 times, it should be yours too.

IX. THOU SHALT review thy records schedules yearly and renew expiring schedules before they lapse (10 years after effective date).

In Wisconsin this is easy, because the Public Records law requires schedules to be renewed every 10 years in order to remain in effect. Fine… but the City of Milwaukee didn’t follow the procedures of the state records law for a long time with regards to schedule adoption, with the result that there are many, many schedules in my database that don’t have any expiration date at all. Even if the 10-year sunset period didn’t exist, however, it still would be a good idea to go through schedules periodically and make sure that they all reflect current workflows and legal and administrative needs, so I am not sure why that wasn’t done (Well, aside from the fact there were 5000 of them). So now I am doing the renewal and related research on updating schedules largely all at once for Department records, which does help me get a sense of what the different departments do or did. I would definitely rather do this a bit at a time rather than all at once, though.

X. THOU SHALT make the City Records Officer aware of any state, federal, or industry-specific legislation or regulations affecting retention or confidentiality of your series.

This Commandment is why Records Coordinators are so useful in the first place—they have knowledge of the specific industry or functional context of their own records in a way that a centralized records manager never will. As such, when writing retention periods, knowledge of any laws/regulations/etc. that govern the creators’ need to keep records around for a specific period of time is invaluable. Records Managers can, of course, look for inspiration in other institutions’ schedules for similar records, as well as in statutes and regulations they’re already familiar with for setting retention and privacy levels… but why go to the trouble if the records coordinator can just tell you “our professional organization suggests keeping these for 6 years”?

Good list! I would only add this to your discussion of Number II (not scheduling non-record if official copy scheduled elsewhere). If people ask to schedule what appear to be duplicates, make sure they are true duplicates. And actually do not contain additional information that makes them a new and different record from the one held by the official record holder. This sounds routine but can get complicated.

For example, the official record holder may send out a record to internal recipient as FYI rather than seeking comments. The unnannotated versions received by everyone on the router need not be scheduled as separate records.

But say John Doe, the sender, has a reputation for suppressing written dissent and preferring “public relations” versions of records kept in his or her office. An internal recipient may annotate electronically or by hand and quietly preserve the original received record with a note. The note says “The information in the first bullet point is inaccurate. Jane Smith in Office A tells me x actually should be y. I talked to John Doe about the inaccuracy but he wants this to represent the official position. We were unable to get a fix.”

This annotated version obviously creates a new record and possible a new series of dissent records. Whereas the higher level official may prefer to represent deliberations as preserved only in a file that his office generates and controls as author of the distributed version. This isn’t textbook or universal–but it can happen.

The records manager needs to be aware of pre-emptive sanitization efforts and if able (not all are, this depends on understanding of organizational culture) ask holders of copies is there is a particular reason why the version they hold warrants a separate schedule item. “Dissesnt” records recording verbal interactions are historically valuable but their scheduling can be fraught. So asking a few questions rather than replying automatically that “non-record” need not be scheduled gives you context–at least is settings where understanding context isn’t risky for all.

With the disclaimer that these are necessarily simplified for use by non-professions, this is a very good point. My usual rule-of-thumb for getting around this is to say that as soon as you make alterations to a record, it becomes a new record and you have to manage it accordingly. This is not a perfect solution– if you’re notating records for a series your office doesn’t control you get into provenance questions e.g.– but it’s better than nothing.

Wisconsin offers an additional wrinkle, in that drafts prepared for *personal* use are specifically excluded from the definition of a record. 9 times out of 10 this saves the RM/Archivist from a major headache, but in the situation you mention that’s a document that warrants possible retention. Will the records creator have enough presence of mind to tell the RM about such valuable annotations? Um… Maybe? Another case where training is absolutely critical.

Well said, Brad. Training is criticial, training with contextual sophistication even more so. As I’ve noted elsewhere, how different employers view risk in and use knowledge (as opposed to information) varies greatly. Over time, the RM learns how to read between the lines, assess organizational culture, and pitch training so it has some chance of resonating. That includes resonating with individuals in business units but also those at the top of an organization, since tone at the top matters here, too. That tone can vary, of coure. In some cases, things can get tricky, which is where astute navigation becomes all the more important for RMs and stakeholders who depend on them