If a 29-year-old Peugeot 309 is the answer, it’s fair to wonder: what on earth is the question? In fact, I had no idea about either the question or the answer when I submitted a “subject access request” to Eldon Insurance Services in December last year. Or that my car – a vehicle that dates from the last millennium – could hold any sort of clue to anything. If there’s one thing I’ve learned, however, in pursuing the Cambridge Analytica scandal, it’s that however weird things look, they can always get weirder.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

Because I was simply seeking information, as I have for the last 16-plus months, about what the Leave campaigns did during the referendum – specifically, what they did with data. And the subject access request – a legal mechanism I’d learned about from Paul-Olivier Dehaye, a Swiss mathematician and data expert – was a shot in the dark.

Under British data protection laws, “data subjects” – you and me – have the right to ask companies or organisations what personal information about them they hold. And, a series of incidents had led me to wonder what, if any, personal information Leave.EU – the campaign headed by Nigel Farage and bankrolled by Arron Banks, a Bristol-based businessman – may have held on me. By the time I submitted my request in December, I’d already been writing about them and their relationship with Cambridge Analytica for almost a year – the first piece in February triggering two investigations by the Electoral Commission and Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO).

But, in November, I appeared to touch a nerve. Leave.EU’s persistent but mostly lighthearted attacks on my work began to change in tone. Conservative MPs had started to criticise the government’s Brexit plans, it had been revealed that Robert Mueller was investigating Cambridge Analytica, and it was in the middle of this that Leave.EU put out a video: a spoof video that showed me being beaten up and threatened with a gun. It was intended to creep me out. And it did. What else, I wondered, did Leave.EU have planned? What else did it know about me? And where had it come from? Companies House shows dozens of companies registered in Banks’s name and variants of his name – Aaron Banks, Aron Fraser Andrew Banks, Arron Andrew Fraser Banks, to name three – including a private investigations firm, Precision Risk and Intelligence Ltd. Andy Wigmore – a director of Eldon and Leave.EU’s spokesman – had told me previously that all insurance firms had access to police databases for fraud prevention purposes.

So, on 17 December last year I submitted a request to Liz Bilney, chief executive of both Leave.EU and Eldon Insurance Services, that asked for the personal information held on me by 19 of Banks’s companies.

The letter triggered a steam of abuse, Banks and Wigmore revealing the contents of my letter in a series of tweets. The next day, I complained to the ICO that my attempt to access my private data, as is my right under British law, had been disclosed publicly and used as the basis to attack me further. The ICO found them to be “likely” in breach of the Data Protection Act and said it had written to notify them. Bilney asked me to pay £170 – you can charge up to £10 for each request by law – and just over a month later I received two folders of data, one relating to the personal information held on me by Leave.EU and the other by Eldon Insurance Services.

The second folder was a surprise. And not just to me. “We have no information on you dopey! You are a political adversary not a customer…” Banks had tweeted at me. And when I’d complained, he said: “You aren’t a customer, we don’t hold any data on you and frankly a journalist asking questions isn’t private, dopey!”

He was right: I wasn’t an Eldon customer. But there it was: my Eldon data, a spreadsheet, that showed it had gathered 12 different sets of data on me from three different sources. These were identified by different codes and a legend supplied with the spreadsheet revealed the codes represented software companies. And there was my data: Eldon had my name, age, address, email address, friends and family who had been on my car insurance and how I had been scored for risk.

How did Eldon have it? And where did it come from? Was I – or had I been – a customer of Eldon at some point? I hadn’t, it turned out, but a search of my inbox revealed that on 27 July last year, I’d taken out car insurance on the basis of a quote I’d obtained from Moneysupermarket.com. The telling detail was that it was sent at 13.34, the same time as the final entry on the spreadsheet.

I had given Moneysupermarket.com all sorts of private information: my home, car, personal relationships, and it had passed that private, sensitive information on to Eldon.

Going back to Moneysupermarket, I could see that I’d consented to my data being shared with its partners when I sought quotes and that, according to the terms and conditions it had set out, it could share it if it wanted.

Two months earlier, I’d spent 72 hours getting increasingly unsettled by the video Leave.EU put out and which, despite hundreds of complaints from people, it had refused to take down. Banks had previously told me that “I wouldn’t be so lippy in Russia” and both he and Leave.EU had made a habit of retweeting personal attacks directed at me by the Russian Embassy’s Twitter account. The video, showing a photoshopped image of me being hit in the face to the music of the Russian national anthem, went up the same week the Telegraph launched an attack on “Brexit mutineers”. Brendan Cox – the widow of Jo Cox – said that it created “a context where violence is more likely”. Another Leave.EU tweet called them a “cancer”. The atmosphere was ugly. And the video felt threatening. I felt threatened. It wasn’t so much that it had been put up, but that it stayed up – only coming down, eventually, when the Observer’s editors intervened.

I tell the story at length because this is the context in which I found out this information. And because it turns out that my experience may not be unique. Moneysupermarket responded: “Our providers use the personal information from our customers to generate personalised quotes for the service they have asked for (such as quoting for car insurance) and are not allowed to use this information for anything else unless they have permission from the customer.”

But I had given my consent and it shared my information in accordance with its privacy policy. In its annual report, it reveals it holds data on 24.9 million people – half the British electorate.

My disquiet about what information companies and organisations hold on me, and how it might be used, is a disquiet that, in the light of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, should perhaps be felt by everyone.

Or at least raise questions. Questions, such as: what private information do Banks’s companies hold on you? Where did it come from? How might it have been used?

Last week an ex-director of Cambridge Analytica, Brittany Kaiser, made explosive new claims in testimony to MPs. She appeared before the select committee for the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and told MPs that, despite ferocious denials repeated for more than a year, Cambridge Analytica did process data for Leave.EU and Ukip. It did carry out work for the campaign, she said.

But she also told MPs – and submitted evidence – that she had been asked to devise a strategy to combine Ukip, Leave.EU and Eldon insurance data to politically profile people. What’s more, she said, she visited Eldon’s call centre and HQ in Bristol, which had also served as the campaign HQ for Leave.EU, and seen with her “own eyes” how Eldon employees used Eldon data to target people with political messages.

If true, Ravi Naik, a human rights lawyer who specialises in data rights, says it would be a scandal on the level of the one now engulfing Cambridge Analytica and Facebook. Because my attempt to find something as benign and unavoidable as a new insurance deal – just like millions of others – for my Peugeot had inadvertently revealed personal data they potentially had access to.

“It’s what Christopher Wylie has been saying about the weaponisation of data,” says Naik. “The idea that by doing something fundamental to your day-to-day life could have led to sensitive personal information being used in ways you don’t know about, let alone consented to.”

Banks told the Observer that Kaiser’s evidence “was a tissue of lies”, that she had visited Eldon’s offices only once, that the call centre handled calls from the public or those who followed Leave.EU on social media, and that the company “absolutely refutes” that any insurance data was used in the campaign. He said: “Eldon has never given... any data to Leave.EU, they are separate entities with strong data control rules. And vice versa.”

The folder containing my Eldon data was one of two I received back. The other marked Leave.EU contained all sorts of odd material: emails I’d sent Banks and Wigmore, and replies they’d sent to me. Emails they’d sent employees about me. Emails about mocking up Photoshopped images of me to put out on Twitter.

Typical is this one from 13 December, in which Wigmore writes: “Can we get a picture of carole codswallop accepting her award Oscar style thanking the Russians, Facebook Arron and myself with caption only 75p spent on Brexit etc – make it funny.”

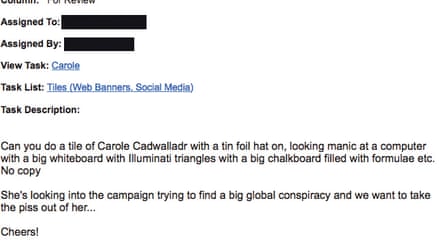

Or this one from May last year, four days after the Observer published the first story that used Wylie, the Cambridge Analytica whistleblower, as an anonymous source: “Can you do a tile of Carole Cadwalladr with a tin foil hat on, looking manic at a computer with a big whiteboard with illuminati triangles with a big chalkboard filled with formulae etc. No copy. She’s looking into the campaign trying to find a big global conspiracy and we want to take the piss out of her…”

He did. The image – flatearth.jpg – is attached in the next email and later @LeaveEUOfficial put it out on Twitter. “Madwoman @carolecadwalla is desperate to unearth some global conspiracy to undermine the #EURef. There isn’t one. Leave won, get over it!”

So far, so predictable. The “piss taking” was – until November’s video – the main mode of communication from Leave.EU to me. But the email chain and others in the folder pose more questions. Questions about the relationship between Banks and Leave.EU. About the relationship of Banks with Eldon insurance. And their relationship to each other. Questions that urgently need answers.

Because the request to Leave.EU was assigned to an employee whose email states “(Eldon Insurance Services)” and who has worked for Eldon Insurance Services Ltd since October 2016. He was assigned the “task” by someone with a Leave.EU email address and the email links through to a password-protected website called www.eldoninsuranceservices.eu.teamwork.com.

Also cc-ed is another employee who Kaiser’s emails, released via parliament last week, show was involved with the work that Cambridge Analytica did for the campaign. His LinkedIn profile describes him as doing political work on behalf of Eldon Insurance.

Other employees are listed as working for working both companies. Eldon’s operations manager, for example, is also Leave.EU’s operations manager. When asked about this crossover of employees, directors and projects, Banks said: “During the campaign a small number of managers were allocated, expensed in the EC [electoral commission] return and worked on Leave.EU.” When asked about current employees, including current employees who were working for both organisations concurrently, he gave no reply.

Leave.EU was, and still is, based within Eldon Insurance’s HQ. Westmonster, the political news site Banks founded and funded, is registered to an Eldon Insurance address. Adverts for his firm GoSkippy are routinely sent to people on Leave.EU’s mailing list. Last year, Banks defended the practice, saying: “Why shouldn’t I? It’s my data.” When asked again last week, he said: “Leave.EU after the referendum campaign carried the occasional ad for insurance, so what?” In an email a day later, he said: “Eldon has never given ... any data to Leave.EU.”

Last week, the Observer revealed that in the same week that the ICO had raided Cambridge Analytica’s office and seized evidence, it had issued “information notices” to both Leave.EU and Banks, a regulatory action that asks for information to be provided, for which non-compliance is a criminal offence. The questions are being asked, it seems. However, Elizabeth Denham, the information commissioner, told a conference last week that it urgently needed stronger powers to conduct its investigations. “We need the regime to reflect that data crimes are real crimes,” she said.

The questions are out there. Whether the ICO has the power to get the answers – or whether we’re going to continue to rely on clues obtained by a parliamentary committee and a 29-year-old Peugeot – remains to be seen.